Tribal claims against the Vedanta Bauxite Mine in Niyamgiri, India: What role did the UK OECD National Contact Point play in instigating free, prior and informed consent?

by Shelley marshall and Samantha Balaton-Chrimes

This case study provides an examination of the interaction between international and local judicial and non-judicial redress mechanisms in the work of the Dongria Kondh and Kutia Kondh to protect their land rights and the environment. The Vedanta Aluminium Complex project was proposed and partially initiated by subsidiaries of Vedanta Resources Ltd, a UK-listed company that operates in many countries around the world.

Issues:

The complex involved a proposal to establish a Bauxite mine at the top of Niyamgiri Hills in Kalahandi and Rayagada districts, an alumina refinery in Lanjigarh at the bottom of the Niyamgiri Hills and by one of Odisha’s most important rivers, and a smelter in Northern Odisha. The Niyamgiri Hills constitute the only traditional home to the Dongria Kondh and the Kutia Kondh. The Dongria Kondh and Kutia Kondh aimed to claim their right to control over their lands, and to exercise free and informed consent concerning any transfer of their lands.

Non-judicial redress mechanisms:

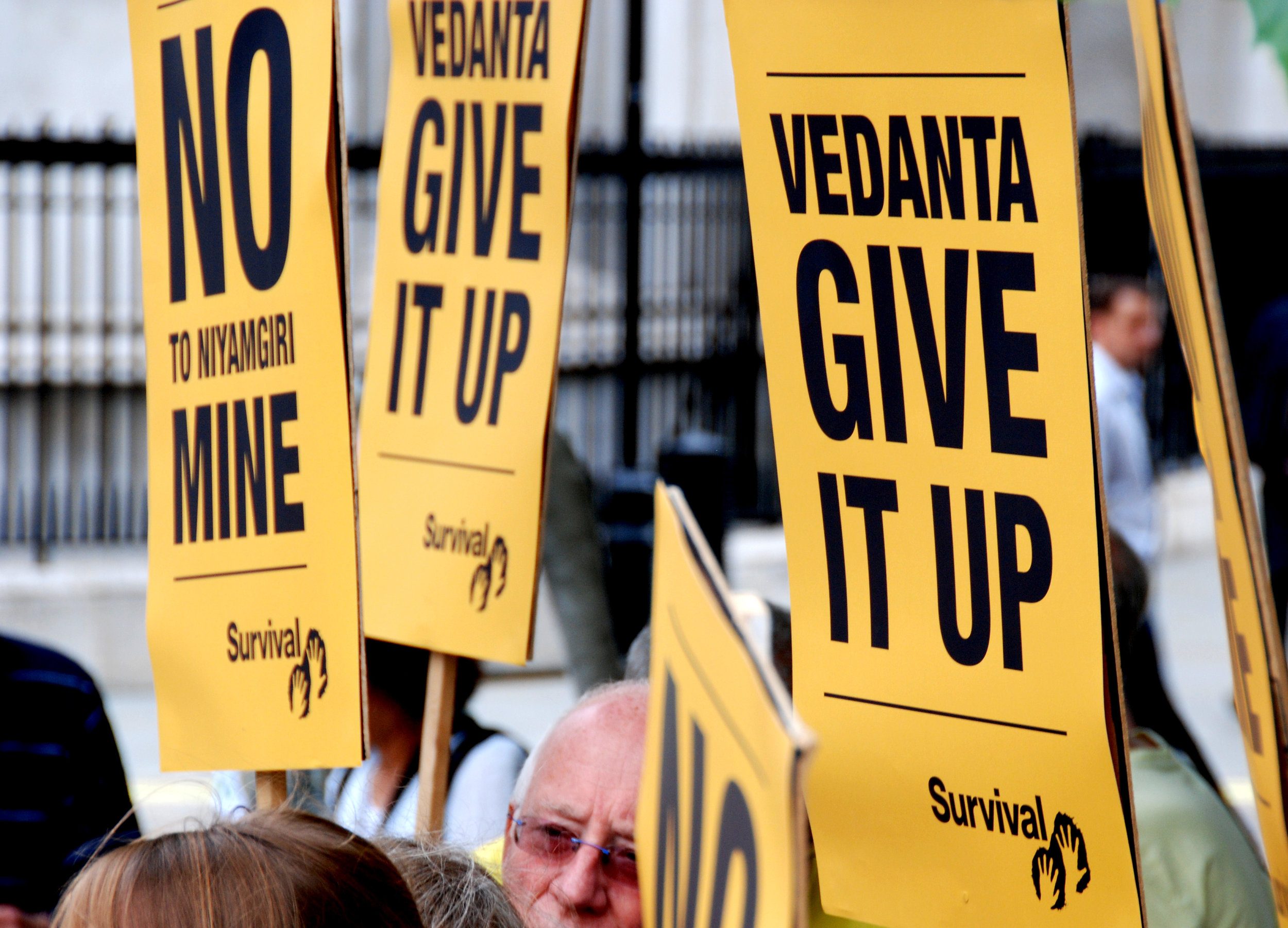

Survival International lodged a complaint to the UK National Contact Point. At the same time, a complex set of administrative reviews and court cases were being lodged and heard in India, backed by an incredibly committed network of local supporters.

A determination against Vedanta by the UK National Contact Point (‘NCP’) led to the disinvestment of a number of shareholders and reputational damage for Vedanta on the international stage. At home, the pursuit of legal means of redress resulted in a process of self-determination for tribal people underwritten by constitutional law, rather than soft international norms. There is little evidence that the NCP determination influenced administrative and judicial decisions in India, although interviews indicate that the Environment Minister was aware of the determination and that it may have bolstered his resolve to block the mine. Ultimately, the mine was stopped by a Supreme Court of India judgment to send the decision regarding the mine back to the lowest level of government in India - the Gram Sabha. This process can act as an international model for a democratic means of free and prior informed consent.

An executive summary of the report can be read below.

EXECUTIVE SUMARY

Aim of this report

1. Drawing primarily on field work conducted from 2012 to 2013, the report examines the role that the UK National Contact Point (UK NCP) played in providing redress to tribal communities affected by a proposed mine in the Niyamgiri Hills, in the district of Kalahandi, located in the eastern Indian state of Odisha. The UK NPC is a non-judicial human rights mechanism created in accordance with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The case was filed by Survival International, a UK based non-government organisation on 19 December 2008. The case was able to be brought before the UK NCP because Vedanta, the transnational resource company in this case, was listed on the UK stock exchange.

The proposed mine and its impact

2. The mine was proposed as part Vedanta’s aluminium production complex. A greenfield aluminium refinery at Lanjigarh, at the foothills of the Niyamgiri hills, became operational in 2008. The mine would supply bauxite to the refinery.

3. The proposed mine and aluminium complex are located within a region of great ecological importance, around 450km away from Bhubaneswar, the capital of Odisha. The Niyamgiri Hills are home to tigers, leopards, elephants, sloth bears, pangolins, palm civets, giant squirrels, mouse deer and sambar deer, most of which are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature red list of endangered species. It is also a part of migration corridor of elephants between the forests of Kondhmals and of Kalahandi/Koraput. The region is home to tribal communities who have inhabited the area as long as documentation exists. This report concerns the human rights grievances of the Dongria Kondh who inhabit the Niyamgiri Hills.

4. The Niyamgiri Hills are not only the home of the Dongria Kondh, they constitute a sacred cultural and religious site for them. Vedanta’s mining operations in the Niyamgiri Hills raised significant human rights concerns, including the failure to acquire free, prior and informed consent for land acquisition, indigenous rights, environmental rights and subsequent damages to human health.

The campaign to gain redress for the Dongria Kondh

5. This report examines the complex and sustained campaign against the bauxite mine. Since the Memorandum of Understanding between the state of Odisha and Vedanta for the mine was signed in 2003, Vedanta has been embroiled in a spate of complex of legal disputes, spanning multiple jurisdictions and involving access to a variety of political, judicial and non-judicial redress mechanisms.

6. A kind of pincer movement extended between a broad range of actors involved in local and international campaigns. International and domestic pressure was simultaneously placed on Vedanta in respect of the project. On one hand, an international advocacy campaign was launched by a number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including Amnesty International, ActionAid and Survival International, with strategies including the lodging of the UK NCP complaint and a lobbying of shareholders. At the same time, a complex train of administrative reviews and court cases were being lodged and heard in India, backed by an exceptionally committed network of local supporters. The report describes the large range of redress strategies pursued by different stakeholders, and analyses the efficacy of these strategies, both individually and in their cumulative effect.

Outcome of the UK NCP decision

7. The UK NCP made a determination on 25 September 2009 that Vedanta had breached the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

8. Strong and compelling evidence exists that the UK NCP determination against Vedanta was a major reputational blow for the company, which led to well publicised disinvestment by a small number of Vedanta’s shareholders. This was primarily due to campaigning conducted by high profile UK NGOs to highlight the NCP’s final statement (determination) and convince shareholders to disinvest on ethical grounds.

9. The report finds that, although this was in some ways influential, the effectiveness of the NCP’s decision would have been much stronger if further steps to harness the leverage of the NCP and the UK Government, more broadly, had been taken. At the very least, coordination, or some communication ought to have occurred between the UK NCP or the UK government and relevant Indian departments and the decision ought to have been more widely communicated to stakeholders in Odisha.

10. The NCP’s decision, combined with lending to Vedanta by Equator Principle Banks being conditional on evidence of reform, led to a number of internal policy changes within Vedanta, with a view to becoming more sustainable and respectful of human rights in the future.

11. These reforms within Vedanta did not lead the company to desist from pushing for full access to bauxite from the Niyamgiri Hills by pressuring the Odisha state government via legal means. Nor has it resulted in Vedanta desisting from pursuing bauxite from other sources which will also likely negatively impact tribal communities. A fact-finding mission to Odisha conducted by Survival International, lodged with the UK NCP on 23 December 2009, concluded that Vedanta had done nothing to implement the recommendations contained in the Final Statement by the UK NCP.[1]

12. There is little evidence that the NCP determination influenced administrative and judicial decisions in India, though some interviews for this study indicate that Environment Minister at the time, Jairam Ramesh, was aware of the determination and it bolstered his resolve to block the mine.

A precedent for Free, Prior and Informed Consent is set through Indian courts

13. International law concerning indigenous people requires that indigenous people have consent, as opposed to consultation, enabling them to veto a project.[2] This is known as free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).

14. Ultimately, the mine was stopped by a Supreme Court of India judgment to send the decision about the mine back to the lowest level of government in India — the Gram Sabha or village council. A Gram Sabha consists of every adult of the village over 18. Though a Gram Sabha had already been held on 26 June 2002, it was marred in controversy with allegations of corruption and intimidation and convened under weaker laws. Voting on the transfer of land for the mine occurred a second time in 2013 through secret ballot under the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 (‘Forest Rights Act’). The 12 villages voted unanimously against the mine.

15. It was the first time that the Forest Rights Act had been invoked to address issues of collective, community claims, affirming a determinacy and a jurisdiction for tribal rights (or indigeneity).[3] It was also the first time that a provision of ‘community consent’ extended beyond the provisional ‘duty of consultation’ to include a power of veto and exclusion.

16. India’s newly empowered Gram Sabhas could serve as a model for best practice in free, prior and informed consent. The process represents a useful model to ensure that such decisions are made as close to the citizen as possible — vesting the community with the power to decide its own fate with respect to mineral extraction and the transfer of land.

Barriers to seeking redress for remote communities

17. Regardless of the positive nature of the outcome in this case, breaches of human rights continue both in Lanjigarh, in the area of the refinery and the Niyamgiri Hills. A marked corrosion of living conditions has been documented since 2004, when the refinery was built and the mine was first approved. An environment of conflict and intimidation prevails. Yet to date, the Dongria Kondh have succeeded in defending their land.

18. The Odisha state government persists in attempting to gain access to the bauxite in the Niyamgiri Hills through judicial avenues. On 6 May 2016, the Supreme Court rejected a petition by the Odisha Mining Corporation seeking the reconvening of Gram Sabhas in the Niyamgiri Hills to consider the mining proposal that the Sabhas had rejected in 2013.[4] On the one hand, this demonstrates the determination of the Odisha state government to mine the Dongria Kondh’s land. On the other hand, the 2016 Supreme Court decision reinforces the legitimacy of the Gram Sabhas as an institution of democracy and the authority of its earlier decision.

19. The case study points to the immense barriers that stand in the way of remote and vulnerable communities gaining redress and having the law enforced against powerful multinational business. It took over a decade of determined local and international efforts by some of the most authoritative and experienced human rights NGOs within India and globally to achieve the outcome of stopping the mine. Almost every court, administrative body and non-judicial body that the matter came before found in favour of the Dongria Kondh and remarked upon the failure of Vedanta and the Odisha Mining Corporation to adhere to state and national laws and international human rights norms. It is remarkable then that it nevertheless required a campaign on an international scale and extraordinary efforts on behalf of one of India’s best-known human rights legal teams to revoke permission for the mine.

Important lessons for non-judicial mechanisms and business

20. A key aim of non-judicial mechanisms ought to be to promote learning by business about how to respect human rights across all their business activities.

21. The Vedanta case study offers important lessons for business. It shows that when consent for business activity that will impact communities is not gained properly and in keeping with the law, this leaves the business open to sustained disputes in various forums and significant business uncertainty. In this case, because Vedanta invested significant funds building a refinery on the basis that it would have a secure a supply of bauxite, the company was locked into a strategy of pursuing the mine or alternative sources of bauxite. This was an aggressive and risky strategy on behalf of the company. The company would have lost far less money if it had first gained genuine consent from local communities in accordance with the law, and then made decisions about the wisdom of investing in building a refinery.

22. Further lessons for communities, NGOs, non-judicial mechanisms and business are discussed at the conclusion of this report.

[1] OECD Watch, Survival International vs Vedanta Resources plc (19 December 2008) <http://www.oecdwatch.org/cases/Case_165>.

[2] James Anaya, 'Indigenous peoples' participatory rights in relation to decisions about natural resource extraction: the more fundamental issue of what rights indigenous peoples have in lands and resources' (2005) 22(1) Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law 7; JojiCarino, 'Indigenous Peoples' Right to Free, Prior, Informed Consent: Reflections on Concepts and Practice, ' (2005) 22 Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law 19; Marcus Colchester and Maurizio Farhan Ferrari, Making FPIC Work: Challenges and Prospects for Indigenous Peoples, Forest Peoples' Programme No(2007); Marcus Colchester and Fergus MacKay, 'In Search of Middle Ground: Indigenous Peoples, Collective Representation and the Right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent' (Paper presented at the 10th Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Oaxaca, Mexico; Brant McGee, 'The Community Referendum: Participatory Democracy and the Right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent to Development' (2009) 27(570) Berkeley Journal of International Law.

[3] Rajshree Chandra, 'Understanding change with(in) law: The Niyamgiri case' (2016) 50(2) Contributions to Indian Sociology 137.

[4] Ashish Kothari, ‘Decisions of the People, by the People, for the People’, The Hindu (Chennai), 18 May 2016.