OECD National Contact Points: Better navigating conflict to provide remedy to vulnerable communitie

by DR shelley marshall

Each country that is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ‘OECD’ is obliged to set up an NCP office, which is responsible for promoting and implementing the Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by disseminating information and hearing complaints regarding alleged breaches by companies. Our report adds to the growing literature on NCPs by examining the efforts to gain redress in practice rather than only examining the formal characteristics of NCPs.

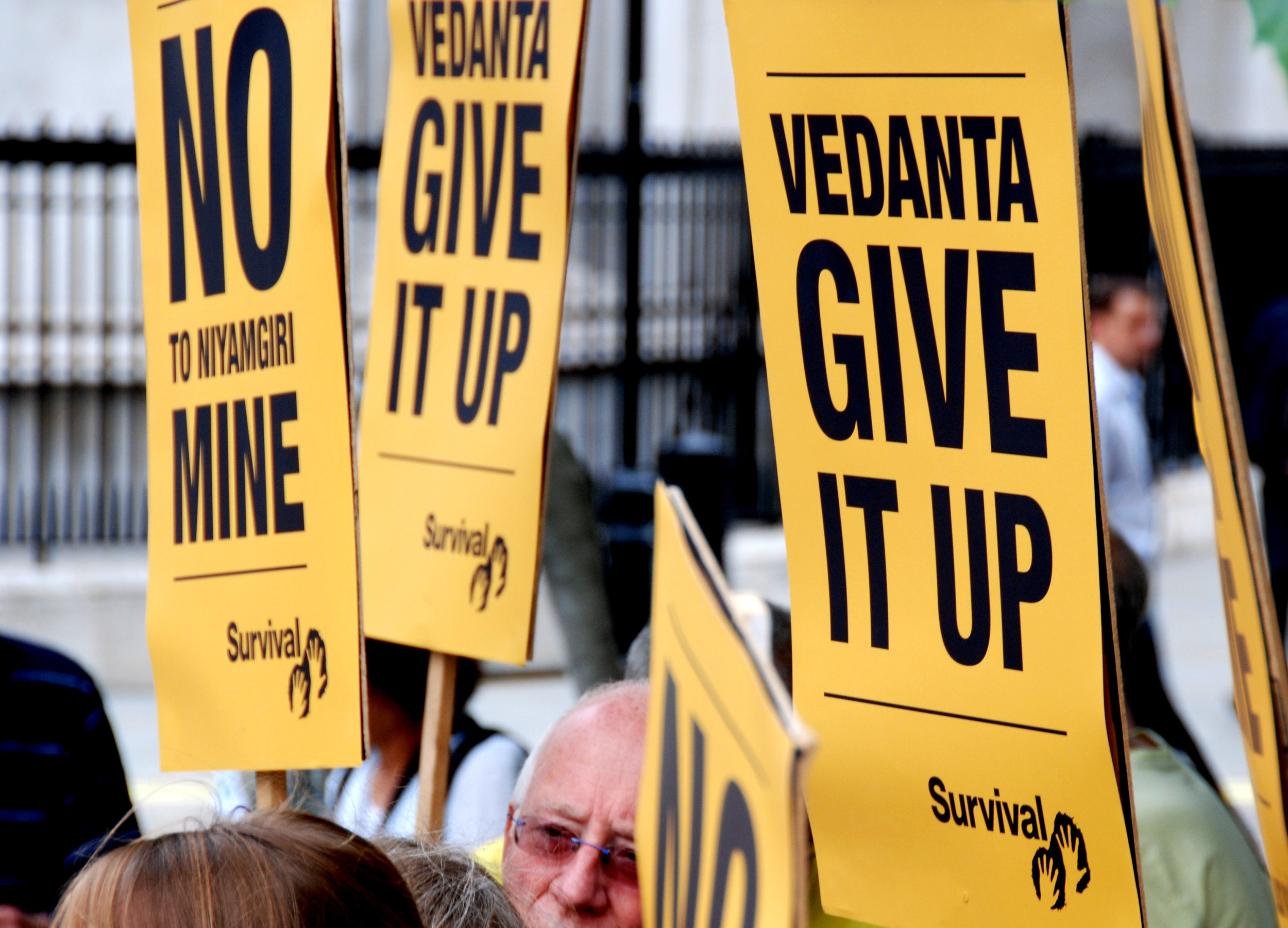

NCPs often consider complex and sensitive cases. In both case studies discussed in this report - the POSCO and Vedanta cases - human rights grievances were experienced by vulnerable and remote communities in the state of Odisha in India. Violence was experienced by community members whom the complaints concerned. A number of the community members and their supporters who objected to the business practices in both cases were killed, and many were injured or jailed. Conflict between communities, business and government had been raging for many years before the complaints were lodged with the respective NCPs. Navigating such conflict is extremely challenging. It requires high levels of expertise, thoughtfulness and flexibility in processes.

NCPs differ in utility from country to country in their capacity to navigate such complexity, with some being much more effective avenues of redress than others. NCPs have significant potential to provide greater access for victims of human rights abuses to effective remedy when that harm is caused by transnational business. They could be an important mechanism for realising the third pillar of the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: the right to remedy. Our research shows that because these redress mechanisms are part of government and determinations are generally made by panels constituted by respected experts, they have considerable legitimacy, and as such can attract media attention and generate leverage for those seeking redress for breaches of human rights by business. For this potential to be realised, NCPs require strengthening in a number of respects outlined in this report.

In summary, these areas include:

independence from government;

greater leverage or enforceability;

within government coordination;

cross-country coordination of NCPs;

encouraging long term improvements in human rights practices in businesses;

coordination with institutions in the country where the grievance occurred;

monitoring of mediated agreements;

outreach to increase accessibility for vulnerable communities and workers;

transparency; and

frequency of NCP peer reviews.

The executive summary of the report can be found below.

Executive Summary

Each country that is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ‘OECD’ is obliged to set up an NCP office, which is responsible for promoting and implementing the Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (‘Guidelines’) by disseminating information and hearing complaints regarding alleged breaches by companies.[1] This report adds to the burgeoning literature on the role and effectiveness of NCPs by examining the efforts to gain redress in practice rather than only examining the formal characteristics of NCPs.

The analysis presented in this report occurs at three different levels: The first level incorporates a general overview of the performance of NCPs from different countries, drawing on publicly available documentary sources and focussing particularly on best practice. The second level provides a more detailed overview of the Australian and UK NCPs. The third level entails a more intimate examination of claim making in action. To enable us to explore the dynamics of the way that claims are made and NCPs handle grievances in more depth, the report draws on primary empirical research concerning two vulnerable and remote communities that attempted to gain remedy from National Contact Points: the Vedanta and POSCO cases.

NCPs often consider complex and sensitive cases. In both case studies discussed in this report human rights grievances were experienced by vulnerable and remote communities in the state of Odisha in India. Violence was experienced by community members whom the complaints concerned. A number of the community members and their supporters who objected to the business practices in both cases were killed, and many were injured or jailed. Conflict between communities, business and government had been raging for many years before the complaints were lodged with the respective NCPs. Navigating such conflict is extremely challenging. It requires high levels of expertise, thoughtfulness and flexibility in processes.

NCPs differ in utility from country to country in their capacity to navigate such complexity, with some being much more effective avenues of redress than others. NCPs have significant potential to provide greater access for victims of human rights abuses to effective remedy when that harm is caused by transnational business. They could be an important mechanism for realising the third pillar of the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: the right to remedy.[2] Our research shows that because these redress mechanisms are part of government and determinations are generally made by panels constituted by respected experts, they have considerable legitimacy, and as such can attract media attention and generate leverage for those seeking redress for breaches of human rights by business. For this potential to be realised, NCPs require strengthening in a number of respects outlined in this report.

When compared with other mechanisms and litigation, NCPs have six major strengths, which are explored in this report. These qualities are stronger in some NCPs than in others. This report describes the NCPs in which these strengths are most prominent and how other countries’ NCPs are failing to meet their potential. The six strengths are:

1. ease of complaint lodgement and broad formal rules of standing;

2. broad interpretation of human rights standards;

3. acknowledgment of business responsibility for supply chains and investments;

4. acknowledgment of positive duties to mitigate harm for businesses in relation to human rights;

5. high degree of legitimacy in findings; and

6. cost-efficient and timely in comparison to litigation.

NCPs require improvement in many respects in order to act as more effective avenues for redress. Some of these areas of improvement would not be costly to implement and are readily achievable by government. In summary, these areas include:

1. independence from government;

2. greater leverage or enforceability;

3. within government coordination;

4. cross-country coordination of NCPs;

5. encouraging long term improvements in human rights practices in businesses;

6. coordination with institutions in the country where the grievance occurred;

7. monitoring of mediated agreements;

8. outreach to increase accessibility for vulnerable communities and workers;

9. transparency; and

10. frequency of NCP peer reviews.

Our research suggests that there are great benefits to NCPs’ being housed within, supported by and working closely with government. However, scepticism has been expressed regarding the independence of NCPs and this may undermine their authority. [3] Under the Guidelines that govern the constitutions of NCPs across OECD countries, NCPs are required to operate impartially throughout the ‘specific instances’ process.[4] However, the structure and location of an NCP can influence how it handles a complaint. Some NCPs, such as Australia’s, are housed in and managed by a single government department, with decision-making ultimately sitting within that department, and this can result in conflicts of interest. For example, if a complaint is brought against a company that is a government contractor, or the government is pursuing certain foreign policy aims or industry growth, this could lead to a conflict of interest in the specific instances process.[5] Steps could be taken in each OECD country to ensure that NCPs operate in a way that reduces these conflicts of interest without losing the benefits of government support and authority.

NCPs do not have any powers of enforceability and cannot impose penalties on companies or award compensation to victims. Businesses found to be in violation of the Guidelines are not under any obligation to participate in the NCP process or to follow the recommendations of the NCP.[6] As such, NCPs are seldom useful for stopping a project or other business activity that will infringe upon the human rights of an individual or community. However, our research suggests that NCPs may provide an important opening for negotiation where other requests for negotiation have proved futile and where complainants have raised concerns about ‘how’ a business operates.

NCPs are uniquely situated to deploy forms of leverage to influence business behaviour that are available to them due to their location within government. These types of leverage could include the staying of import or export licenses, the withholding of government subsidies and aid, or disqualification from government procurement. If NCPs were to use such means to penalise offenders and steer business behaviour they would become extremely powerful means of human rights remedy and promotion.

Leverage should be used to encourage long-term behavioural change, not just to address individual grievances. Research reported in other reports in this series shows that many mechanisms and processes for encouraging human rights compliance require enterprises to demonstrate the adoption of corporate accountability practices across the company or broader compliance with human rights standards. These processes can have a much broader positive impact on the human rights performance of enterprises. If NCPs continue only to address single instances, a crucial opportunity will be missed for government to encourage better human rights practices across the whole business in the long term. A further danger is that NCPs will unwittingly entrench harmful human rights practices. In one of the case studies conducted in this report, for example, we find that POSCO developed some voluntary human rights commitments following the NCP complaint against it. However, this did not lead to any tangible changes in its business practices across India, the country where the grievance occurred. Instead, the experience of engaging with the NCP may have equipped POSCO with tools to deflect criticism without making real changes in the way it interacts with communities impacted by its operations.

To achieve this type of long-term change, coordination is not only required across government departments but also with the governments of the countries in which the harm is occurring. This can occur, for example, through information sharing, facilitating fact-finding missions to feed into mediation processes, shared discussion of findings and various other types of meaningful outreach.

One of the strengths of NCPs is the ease of complaint lodgement, including the broad rules of standing. In formal terms, NCPs are highly accessible. However, inadequate funding diminishes the capacity of NCPs to provide outreach to the vulnerable communities that most need assistance to access remedies. It also reduces their ability to conduct investigations which might overcome barriers for vulnerable communities in presenting evidence. It restricts the capacity of NCPs to conduct follow-up meetings or conduct mediations in the place that the grievance took place. This makes NCPs less accessible in practice. The two case studies discussed in this report show that communities that suffer grievances at the hands of transnational business are often in remote locations, and have little chance of knowing that the NCPs might offer an avenue for redress. Unless these communities are provided with assistance to access the mechanisms, including help with constructing the claim, this crucial means for redress is lost to them. Our research suggests that the NCPs that are better funded handle many more disputes than those that receive less funding. This is not because multinational enterprises based in the countries with well-funded NCPs have worse human rights records, but rather because those NCPs are more proactive and accessible. Most NCPs act with no recognition of the disparities in power and resources between claimants and business respondents. The failure to consider such disparities further diminishes the capacity of NCPs to deliver justice to those who most need it.

NCPs could increase their accountability and improve their effectiveness through greater coordination with NCPs in other countries and regular peer reviews. The POSCO case examined in this report, which entailed complaints to three NCPs, demonstrates the problems that arise from failure to coordinate across NCPs when complaints are made about the same grievance. Inconsistent application of the Guidelines diminishes the legitimacy and authority of NCPs. Peer reviews are one way to overcome problems of this type and enhance the sharing of best practice across NCPs.

At its end, this report makes a number of recommendations as to how NCPs can be strengthened to become more effective avenues for redress. It is hoped that these recommendations contribute to future reform processes. Political will plays an important role in the effectiveness of the NCP as an avenue for redress, and accordingly the strengthening of NCPs depends on the genuine concern for human rights in every OECD country. NCPs often offer the only way for aggrieved individuals to seek justice for human rights breaches performed by businesses domiciled in OECD countries. It is critical, therefore, that governments properly resource them so as to realise their potential influence in the field of business and human rights.

[1] OECD, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Publishing, 2011) (‘Guidelines’).

[2] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework’ (June 2011).

[3] OECD Watch, NCPs <http://oecdwatch.org/oecd-guidelines/ncps>.

[4] Department for International Development, ‘UK National Contact Point Procedures for Dealing with Complaints brought under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’ (Media Release, 28 April 2008) 4 <http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/biscore/business-sectors/docs/u/11-1092-uk-ncp-procedures-for-complaints-oecd.pdf>.

[5] OECD Watch, ‘The OECD Guidelines for MNEs: Are they 'fit for the job'?’ (Media Release, June 2009) 7.

[6] Christian Aid, Amnesty International UK & Friends of the Earth, ‘Flagship or failure? The UK’s implementation of the OECD guidelines and approach to corporate accountability’ (Media Release, January 2006) 27 <http://www.christianaid.org.uk/images/F1167PDF.pdf>.